A Wrinkle In Time Glasses

MEG MURRY, the angry, bad-mannered heroine of Madeleine Fifty'Engle's 1962 novel A Contraction in Time, is "blind as a bat." She says so in ane of her first conversations with her new friend, the lanky and earnest Calvin; later on, the mystical Mrs. Who describes her with the same phrase. Meg'south incomprehension, in L'Engle'due south dearest story, is simultaneously fact, symbol, and misdirection: factually, it's true that her eyes can't function without her glasses; symbolically, her poor vision represents to the reader the myopic outlook on the earth that, over the course of the novel, 1000000 must overcome; but also — and hither's the misdirection — as L'Engle surely expects us to call back, bats aren't blind. They simply don't encounter with their eyes, in the human way: instead, they auscultate the globe through other, maybe richer, senses. At a key moment in the novel — which importantly does not appear in Ava DuVernay'southward recent film adaptation — Meg, on an conflicting globe and temporarily blinded by darkness, describes "seeing" as "the most wonderful thing in the world." "What a very strange world yours must exist," Aunt Beast, One thousand thousand'south conflicting protector, lovingly chides.

Meg Murry, the central grapheme in DuVernay's pic, too wears spectacles. At the movie'due south moment of moral crunch (this the first of several coming spoilers), Movie Million's glasses are knocked from her face, and for a moment the photographic camera loses focus, emulating 1000000's blurred eyesight. She clutches her spectacles back to her eyes and sees a vision — an apparition called up to tempt her — of herself, but "better": polished, fashionable, feminine, and with straightened pilus. Doesn't she want to look like this, the evil force tempting her asks? This scene of Meg reckoning with her appearance is not in the book, and its improver to the film is one style to marking the deviation betwixt these ii versions of the story — a deviation intimately bound upward in, simply not reducible to, the representational possibilities opened up by the fact that in DuVernay's diverse cast, Meg is played by the blackness actress Storm Reid.

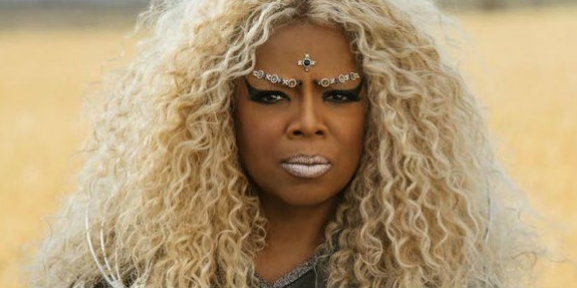

The other metric of departure is Oprah. Oprah is cast as Mrs. Which, a magical character who rarely materializes in the novel, only who in the movie manifests equally a dazzlingly concrete guardian spirit, several stories tall.

Between Meg's eyesight and Oprah/Mrs. Which's embodiment, viewers can nautical chart how Fifty'Engle and DuVernay's stories diverge around their contrasting ethics of the visual. Both 50'Engle's novel and DuVernay'south moving-picture show tell the story of Meg, her biggy younger blood brother Charles Wallace, and her empathic friend Calvin, traveling through time and space to rescue Million's scientist begetter from an encroaching darkness known as the "Information technology," with the help of superhuman beings named Mrs. Who, Mrs. Whatsit, and Mrs. Which. Just in the novel, Meg'southward problem is that she is too preoccupied with how things look to encounter their true essence. In the moving picture, Meg's problem is that she looks at things — most importantly, at herself — the wrong manner.

Thus whereas L'Engle'south novel advisedly parses the limits of the visual, DuVernay'due south movie considers representation as a vital ethical do. Their Wrinkles in Time differently sympathise the human relationship betwixt what we see and how we human action toward each other in the earth. And if both novel and pic take seriously the idea of evil — and they do — they situate that evil very differently in relationship to Meg's story, specifically, to her nigh importantly characteristic, her anger.

What does Meg'south anger take to practice with her advent? What does it have to do with the history of black representation, and what does information technology have to do with the racial politics of 2018? One of the most audacious qualities of the motion-picture show is its existence, itself: Ava DuVernay has made a moral parable that asks all its viewers to consider the power of universal evil through a story almost how black girls and women come across themselves. 50'Engle'southward story becomes more alive to its original questions about evil and customs with DuVernay's perspective immersed within it.

It'south non a coincidence that the most historically situating reference in the picture is a quotation from Hamilton, which, like DuVernay'south Wrinkle in Time, is partially a racial parable almost representation'south foreign temporalities of retrospection and progress: "tomorrow," harmonizes Miranda/Hamilton in 2015/1782, "there'll be more than of us." In this insistent, if also fraught, optimism, DuVernay's moving-picture show runs parallel to Lin-Manuel Miranda's musical in that both stories seek to find a fashion to characterize a racial past without being haunted by it. DuVernay wants to make a movie about blackness joy — to tell a story that is not trapped within black pain, but also not blind to black hurting. (And surely about blackness pain, information technology is Madeleine L'Engle'due south novel — a novel, call up, that is set in 1962, that describes evil and social suffering, and that never mentions race — that truly is bullheaded as a bat.)

This shouldn't exist taken every bit a full endorsement of the movie, which suffers from uneven interim and editing, and thus at times is a little, similar, ho-hum, to lookout. Simply something happens in it that is worth paying attention to.

¤

A certain kind of girl reader — for example, myself — places a high value on books about certain kinds of girls: angry ones. And there were not many books in my childhood that featured a daughter who was as angry as One thousand thousand Murry. 50'Engle'southward Million Murry is, after all, angry all the time. She is angry at her teachers, her school main, everyone in her town, and, most of all, at herself. She thinks of herself in the harshest terms — "One thousand thousand, the snaggle-toothed, the myopic, the clumsy" — and understands herself equally a "delinquent," a "monster." "She looked at herself in the wardrobe mirror and made a horrible face up. […] Automatically she pushed her glasses into position, ran her fingers through her mouse-brown pilus, and so that it stood wildly on finish." Million also badly resents, even as she fiercely loves, her beautiful female parent. "Surely [gossip] must hurt her as it did Meg. Only if information technology did, she gave no outward sign […] — Why can't I hide it, likewise? Meg thought. Why do I ever have to show everything?" Her anger plays out all over her face.

50'Engle's Meg is non simply angry, she is too ugly — a category that you might not believe in, but that L'Engle'due south novel does. In it, some people are beautiful (1000000's female parent) and some are not (One thousand thousand), and at that place's a difference between them and how they're treated (1000000 is reassured that she will someday be beautiful, but never told that she is cute as she is). 1000000, however, much like Jo March, her aroused predecessor with a lovely (and acrimony-managing) mother, does take a "1 dazzler," her eyes, and these are obscured by the coke-bottle glasses that she requires to run into at all. Delight note: The thing that makes her able to meet the globe changes the way she'due south looked at. Equally a young reader in the 1980s, I had to imagine my way into a world where a girl's glasses would exist so thick they would distort her face — just like I had to imagine my way into a world where I was meant to exist overjoyed past Calvin, equally Meg is, when he removes her glasses, stares at her transfixed, wipes her tears, and tells her to put her ugly glasses back on. "Y'all've got dreamboat eyes," he says. "I don't think I want anybody else to come across what gorgeous eyes you have." Meg "smiling[s] with pleasure" to hear this possessive compliment. Information technology was unclear to me, equally a girl, if Meg'southward pleasure was part of her healing or role of her damage.

Storm Reid, who plays Meg Murry in DuVernay's movie, feels similarly angry and messy and clumsy. Similar the novel's Meg, she feels like an outsider, bullied aggressively, if not engaged in the regular sort of concrete gainsay that the character in the novel is. Reid's Meg wants to be non herself.

Merely Reid is also a very beautiful girl, and this is important, considering while Meg in the volume needs to realize that she is not reducible to her physical advent, 1000000 in the flick needs to realize what the viewers can already see: that she is lovely, lovely, lovely. Ugliness in DuVernay's motion-picture show is non a real affair in the manner that it is in Fifty'Engle's novel; or, if it'south existent, it's a thing of attitude and behavior rather than physicality. Meg might feel a visual difference between herself and the pop girls in her school, but there's cipher about her advent that registers her as different, even unfashionable or uncool, to viewers. (Here DuVernay is almost encumbered by Reid'south physical presence: even in scenes that narratively depend on Meg'due south clumsiness, that clumsiness is always clearly a performance put on over Reid'southward graceful move, which we never don't see.)

Certainly at that place is nada uncool nearly her super beautiful glasses. While DuVernay's direction at other points in the moving picture plays with the idea of visual distortion — the picture show's first shot of Meg, for case, shows her through a chalice that skews her confront — Flick Meg'due south glasses practice not warp her face in the fashion that Novel Meg's do. Unlike for Novel 1000000, for Film 1000000 the problem of how she sees is separable from how others see her. It is not, notwithstanding, separable from the problem of how Meg sees herself.

Of course, how she can see herself depends partly on where she is in history. What obstacles will Meg'southward earth nowadays to her attempt to come across herself clearly? The answer is different depending on what year she is in — certainly they would be different in the 1962 of L'Engle's novel than in the 2018 of this movie. But when time, in the pic, feels out of joint — as information technology most dramatically does when 1000000 reaches for a telephone, and it's anachronistically not a prison cell phone but a telephone-phone, plugged into a wall, with a handset and base and long coiling cord — the viewer feels a strange sense of temporal unease that the movie, like many black texts earlier it, understands as racial. Aligning DuVernay's picture with a long history of black literature preoccupied with the question of progress — consider The Fire Next Time, consider Kindred, consider Dearest — viewers can recognize A Contraction in Time'southward strange technological anachronisms equally a device used to demonstrate that fifty-fifty every bit the years motion forward, racial progress might not. (Here my perspective is shaped past my greater familiarity with the history of black writing than with gimmicky black fiction, particularly scientific discipline fiction, but technologies of the hereafter certainly mattered to by literatures, too.) Within this framework, DuVernay's claiming as a director becomes more clear: her movie, I call back, hopes to create a world for her movie's black girl viewers that is honest virtually how it feels to be not at home in history and as well dauntless enough to imagine a hereafter less encumbered past the damage of race.

Information technology'due south this trick — creating a visual world where an honest history of racial impairment can be portrayed without being explicitly shown — that DuVernay needs Oprah Winfrey to accomplish. Oprah, who appears first in this motion-picture show in dazzling, bedecked beauty — enormously tall, in the most astonishing clothes. At other moments, however, specifically when Moving picture Meg gazes at her, Oprah appears in spectacular close-up; long, lingering shots of her eyes and nose and mouth and cheek bones fill up the screen. In these close-ups, DuVernay wants the film's viewers, if not Moving-picture show Meg herself, to encounter a history of everything that Oprah means. This is to say, non but the corporate juggernaut that is Oprah — that is the least interesting thing to say most Oprah, in this context — but rather a black adult female transcendently successful in the now who has achieved success non by rejecting simply existing in tandem with her history of suffering. And, because this is a moving-picture show, the history of suffering she can correspond is not but the item abuse she, the woman Oprah, suffered every bit a kid, only the cinematic history of black women's suffering that Oprah has portrayed. We cannot understand the close-ups of Oprah in A Contraction In Time without seeing them in tension with the faces of black womanhood Oprah has portrayed before — in, for example, The Color Purple, Honey, and DuVernay's own movie Selma. In all of these movies, Oprah has portrayed women of inordinate strength and stamina who are physically and emotionally attacked precisely for the backbone they display in inhabiting their strength.

Oprah, who lent her trunk and her image to the motion-picture show adaptations of ii of the most important novels about black womanhood of the final 60 years, adds something to A Wrinkle in Time that no one else could add: not just does she make it a movie about black transcendence, but she too makes viewers — especially white women viewers, like me — consider L'Engle'south A Wrinkle in Fourth dimension every bit a novel aligned with The Color Purple and Honey, equally a novel that, when looked at through its omissions, contains a story about the price that blackness women pay when white women refuse to see.

In DuVernay's movie, Mrs. Which and One thousand thousand Murry take a special bond they do not have in the novel; they are ii black women trying to reconcile how they experience and what they know. Information technology is essential to Meg's character that she can come across, equally a mentor, a black woman; it is likewise essential to Mrs. Which's character that she can imagine a young black girl who sees her. Mrs. Which is both the opposite of Picture Meg — enormous, confident, knowing — and her parallel: a grown black adult female, taking special care of Meg, who is a young black girl, struggling with feelings of abandonment and fear. This reversal plays out in i of the most important changes to the story's plot. In the novel, "The Mrses" guide Meg and her compatriots to Meg'southward father; in the movie, the Mrses only accompany the children as they seek to discover their mode themselves. Information technology's Million's insight — literally — on which the quest for her begetter, and the attempt to turn back this evil, depends.

The final act of the movie — when Meg, Charles Wallace, and Calvin travel to Camazotz — includes its weakest, least compelling scenes. While the novel grapples with intensely felt Cold War, McCarthy-era fears — oppressive requirements of conformity, dystopic governmental control, surveillance, and violence — that are portrayed as timely manifestations of ongoing human cruelty and evil, the pic portrays the evils of "IT" as strangely later-schoolhouse-specialish, and Camozotz is inhabited not by existent suffering people but only past apparitions — such as Meg's vision of her more beautiful self — designed to torment others but not able to endure themselves. It's difficult not to feel these scenes every bit aggressively depoliticized: rather than attaching Meg's anger to the very real struggles of our moment (Blackness Lives Matter, to take only i possibility) the flick homes in on how, for literal case, mean girls are mean considering they feel fat. At that place'southward a pic I can imagine being made, ane I might have liked better, where evil every bit manifested in systemic racial cruelty more than clearly appears. Simply that imagined movie would have privileged my point of view, rather than the view of the tweens to whom the movie is directed: and from that vantage point, the racialized microaggressions of teenaged meanness have a resonance that adults should be willing to eyebrow.

After all, the power of evil does emerge in the movie — not in lingering attending to evil itself, just rather by reverse impression in DuVernay's fantastic emphasis on black embodied joy. If the scenes of "evil" are the movie's weakest, the scenes of joy are its best. These take to do entirely with Meg's willingness to come across herself as beautiful every bit she is.

Allow me return to the pic scene with which I began: Million's encounter with a vision of herself as a "more than appealing" girl, the kind who might more easily exist loved. This girl does not wear spectacles. She has "fashionable" apparel. And she has straightened hair. Pic Million's hair matters. Rather than existence complimented by Calvin on her eyes, as Book Million is, Movie Meg is complimented on her hair: Calvin says she has great hair, and 1000000, initially, does not believe it. As she becomes more confident over the movie'due south progression — equally she, in an of import scene, sees Oprah with hair like her own — she changes. (At the movie'southward conclusion, when Calvin again compliments her hair, she grins at the compliment — and it's a much better compliment than Novel Calvin'southward possessive praise of Novel Million'south optics: Moving-picture show Calvin's wonderment at Movie 1000000's loveliness makes no territorial claims.)

I am not the person who tin can speak to the question of black hair, but hither is a partial list of texts that tend to the question of pilus as a racial signifier, and that in dissimilar means portray and explain how white America has used hair equally a means to evaluate black girls: Uncle Tom's Cabin, The Bondwoman's Narrative, Our Nig, Ida May, Incidents in the Life of A Slave Girl, The Colour Purple — and, perhaps most importantly for 1000000 Murry'southward hair, Selma, Ava DuVernay's motion picture. Selma begins by showing iv black girls walking through a church, in the instant before they are killed by an explosion — the real life 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. In DuVernay'south delineation of this scene, these four girls spend their final moments on earth talking about their hair.

In the novel, One thousand thousand Murry finally is able to overcome "IT" by turning abroad from appearances and toward love, which exists in an extra-visual state. L'Engle'due south novel, in its climactic scenes, likes the bat's bookish solution to the problem of finding our way: non looking, merely language. Literally, at that moment of triumph, the novel breaks into a prolonged verse form, or hymn — story and characters falling away in the face of transcendent words.

In the parallel scene in the motion-picture show, Storm Reid's One thousand thousand floats ecstatically in time's wrinkle, in the tesseract that is a land not of disembodied comprehension but radical concrete connectedness. The end point of her hero's journeying is this state of gloriously visual apprehension. We see her in a shut-up, as we take seen Oprah. And reader: I cried. I thought most how it's Novel Meg's whiteness that allows her to get a sort of Emersonian transparent sci-fi eyeball — and how Motion picture Meg'due south concrete joyfulness is its ain ecstatic political signal.

¤

I mentioned at the get-go of this essay that DuVernay's A Contraction in Fourth dimension does not offer a very satisfying movie-going experience. It's ironic that a movie that is so much virtually history and time would have such bad pacing; the moving picture besides runs into difficulties trying to make the hyper-exact character of Charles Wallace into a living graphic symbol on the screen. While information technology makes sense, within the scope of this film, to visually insist on Meg'due south loveliness, it works less well narratively to strip Charles Wallace's social oddness from his character. Similarly, information technology's frustrating to not allow the Mrses to look quondam or unkempt (every bit a friend pointed out, Reese Witherspoon's centre shadow is perfect even when she has transformed into a cabbage). It's first-class to remind Million that she is beautiful; might we not also allow aging women to show the wrinkles of their own time?

But amidst all of these qualms, partly what emerges is DuVernay's non-ever-satisfyingingly-resolved, but certainly well-asked, question of how race matters to the visual. Beyond the of import, if obvious, point that DuVernay'due south Wrinkle in Time's various cast allows it to reflect a different earth than the one of L'Engle'south novel, I'm suggesting that DuVernay's attention to the visual as a racially marked category helps explain what doesn't work nearly her accommodation of 50'Engle'due south novel — and, just as importantly, what does. My goal here isn't simply to set 1 account above the other, but rather, to think through what these two stories together help viewers both to empathize and to meet.

¤

Sarah Mesle is Senior Editor at Large at the Los Angeles Review of Books.

A Wrinkle In Time Glasses,

Source: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/meg-murrys-glasses/

Posted by: harrisonourch1959.blogspot.com

0 Response to "A Wrinkle In Time Glasses"

Post a Comment